Prime Healthcare’s philosophy is that all healthcare is local. But when COVID-19 struck, healthcare became very local. Different regions of the country surged at different times, with some hospitals filled to capacity, while others operated business as usual. Some ceased visitation immediately, and some allowed only one visitor at a time, with the proper PPE and guidance in place.

How are patient experience managers providing comfort during a global pandemic while navigating the impact of patient isolation due to visitor restrictions?

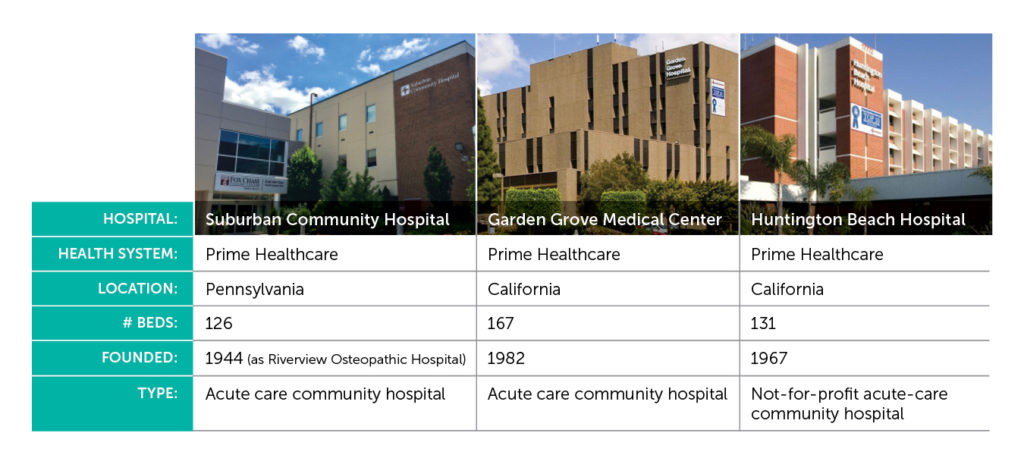

We spoke to two staff members from Prime Healthcare based in different parts of the country charged with improving the patient experience to glean some insights. Kristen Piano is the Patient Experience Coordinator for Suburban General Hospital in Norristown, Pennsylvania, and Jessica LaPalme is the Regional Patient Experience Manager for Garden Grove Hospital Medical Center and Huntington Beach Hospital, in Orange County, California.

How has the patient experience been affected by COVID-19?

Jessica LaPalme:

It’s been tough to not have our regular interactions with patients through face-to-face rounding. I remember when I first started here that patients were so happy during rounds – because they felt the nursing staff cared about them. That’s the power of rounding. One patient told me, “You can go somewhere else for the view, but you come here for the care.” I’ll never forget that because it helped me to truly understand the patient experience at our hospital.

How is your hospital addressing visitation policies as they affect patient experience?

Kristen Piano:

We stopped visitation pretty quickly. When the patients come into the ED, if they come in with somebody, that person needs to stay either in the waiting room or be outside.

It’s been frustrating for the families, patients and our staff, as well. They become frustrated because without the line of communication to the families, there’s a huge breakdown.

A lot of the families are used to in-person, frequent communication with doctors and nurses — that’s not an option now. We need to make sure that communication channel is buttoned up – it’s one of the most important lessons we’ve learned.

LaPalme: It matters what visitors think when they come into the hospital and how they are treated, just as much as how we treat our patients. We’re considering implementing a reservation system for visitors to schedule times to come in for an hour or two so we can stagger their arrival times. Staff would also have to teach visitors how to properly put on and take off PPE.

Another component is setting expectations with patients for how long and often their families can visit. The whole idea of how “open” a hospital is, is something we’re all struggling with.

How are you adapting your communication with patients?

Piano: At first, when we didn’t have as many patients with COVID-19, we were attempting to conduct rounds in person, but from the door. We only did that for a week or two – it was a very strange way to engage with patients. It was especially challenging with our elderly patients who may have hearing problems.

So we shifted to telephone rounding, which was a fairly easy process to implement. We switched over to the COVID script that CipherHealth provided and it’s been perfect for what we need to do.

We’ve also been able to do a lot of service recovery through the calls, and a lot of things are really easy to fix, such as food-related issues.

LaPalme: Every morning, we have a huddle with our case management leaders, the charge nurses on the ICU, and our CNL. In that call, the charge nurses would go patient by patient and deliver any updates, relevant history, and barriers to discharge. My role is to listen closely for what matters need improving, and then I’ll call the patients whenever I have the chance. I’ll always find some time in the day to make patient phone calls.

How can you make telephone rounding more personal when there is no physical proximity?

LaPalme: I definitely wondered about this: how could I really make a connection over the phone? If you start off talking about something else that’s not rounding- or hospital-related, it goes a long way toward building that connection quickly. Everybody that I have talked to on the phone has been extremely appreciative.

Piano: Patients are pleasantly surprised that somebody is calling to check on them. To have a real person call just to talk to them, ask them how things are going – they respond very well to that.

We have a huge patient library that we keep at the hospitals, so when a patient tells me they’re bored without visitors, I ask them, what do you like to read? And then bring them books or magazines, even reading glasses if they need them. I feel like we’ve been able to solve a lot of not-so-big issues, but big to those patients in those moments.

And we’ve solved some bigger issues by speaking with family members outside of the hospital. We’ve had issues with misplaced belongings, and getting hearing aids to patients, for example. I think we have to try anything that we can right now if we can’t be physically rounding with them in person. I’m sure I speak for many who work in the hospital setting: to not feel that connection to the patients is something we’ve never experienced – it’s unheard of before COVID-19. Both patients and staff rely on having that in-person connection.

What are some of the downsides of telephone rounding and how might they be addressed?

LaPalme: The language barrier is something that we’ve encountered. Especially in California, where the population may speak Spanish or Vietnamese, it can be a struggle to connect with these patients. One way around that is to enroll other staff members who speak those languages, and train them to take on rounding in those few instances. Most employees are happy to help, but you need to take it on a case-by-case basis.

Piano: Given that these patients are fairly isolated right now, even the ones that don’t have COVID-19, we decided it was really necessary for us to continue rounding in some way, even if telephone rounding wasn’t what patients were used to.

LaPalme: It also helps when you bring the nurses into the process. I would call the charge nurse in advance of every rounding call to say, “Hey, I’m going to be making some calls to these patients,” so they could expect my call and I could note if there was anyone in particular that needed extra attention. I’ve also had some directors reach out and say, “I’d be willing to make some phone calls,” so people are eager to help us reach out to our patients.

How do you envision the process for telephone rounding evolving as we go forward?

LaPalme: Right now, I have to manually record my notes and then send emails to different departments, so it would be great to be able to leverage CipherHealth’s functionality to send an alert directly through the system.

It would also be helpful to have a streamlined set of guidelines from the corporate level so that other team members could do telephonic rounding using a standardized process. CipherHealth offers some really great examples of scripts to use and I intend to leverage these in the future to streamline across the whole organization.

How do you think the future of healthcare will be impacted as a result of the pandemic?

LaPalme: With COVID-19, there are great opportunities to use technology – like using a tablet for a video conference, or communicating virtually with patients to find out if anything needs to be cleaned. What are the new ways to deal if a call light goes off, instead of having to stop what you’re doing and enter a room? We use technology like this in every other industry, so I’d love to see hospitals catch up.

Aside from their HCAHPS value, I think rounding is really important to keep up. When I call people, they’re just so appreciative. You may see satisfaction scores go up, but just seeing the appreciation from patients and then knowing what to focus on for improvements means more on a personal level.

Satisfaction takes on new meaning during a crisis. New questions become important for hospitals – like, did you have PPE? How is the staff doing, both physically and emotionally? These are the questions that will become important.

One thing that could definitely be improved at any hospital is just more pathways to communication. Since you can’t always pull everyone together at the same time, you need a digital platform to communicate new procedures such as making sure nurses aren’t reusing their gowns, as they might have done at the start of the crisis.

What will the patient experience be like in the “new normal?”

Piano: Patients understand that hospitals had to change their policy — they watch the news, they know what’s going on. I had one patient tell me that when providers go in the room, they have full PPE on and don’t even look human really. Nurses are using baby monitors to watch patients because they can’t go in and out as often and, unfortunately, I think that could be the new normal – at least until there is a vaccine.

How will the role of patient experience manager change as a result of the crisis?

Piano: Our role is critical to the hospital for our patients and their families, as well as for our staff. We certainly bridge that gap. But so much has changed. I feel like it’s a much bigger, more challenging job than it was before. We need to work with our care providers in the hospital and ensure that we’re still getting that valuable feedback.

Of course, policies have to be in place for our patients’ and staff’s safety – that’s our first priority, but what else can we do? A lot of hospitals are exploring solutions to help patients get in touch with families and friends. We need to provide the means so that they feel a little less isolated and can communicate with their loved ones.

To learn more about CipherHealth can help you adapt your rounding processes for the new normal, download our new ebook, Purposeful Rounding in the Time of COVID-19.

See more Customer Stories from CipherHealth.